Sexual Divisions & Synergies

"For masterpieces are not single and solitary births; they are the outcome of many

years

of thinking

in common, of thinking by the body of people, so that

the experience of the mass is behind the single voice” (65).

Points for Reflection

Edna St. Vincent Millay's "I, being born a woman and distressed" (1923)

- does this sonnet strike you as veering more towards the comical or serious?

- does this sonnet adopt an English (Shakespearean) or Italian (Petrarchan) format?

- which emerges more powerfully in the presence of the auditor, the narrator's mental powers or her bodily urges?

- does whatever physical intimacy alluded to here provide a valued, relational consummation?

- what emotion dominates the narrator's feelings following her experience?

- does the poem make clear the gender of the auditor?

Edna St. Vincent Millay's "Love is Not All" (1931)

- does this poem yield to the assumptions of Maslow's hierarchy of needs?

- should "man" in line seven be read as gender neutral?

- does "peace" in line twelve connote peace of mind, or some other form of peace?

- do the circumstances under which the narrator might sell or trade her/his love constitute impossible, absurd conditions?

- why the lines of a sonnet about love with a rehearsal of what love cannot accomplish?

Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own (1928; 1929)

Chp. 3

- an overview of British literary history leads Woolf to conclude that women occupy in poetry and fiction a much more highly respected position than they do in real life (42-44). Does such a disjunction between imagination and reality characterize our own era?

- do you concur with Woolf's provocative claim that "genius like Shakespeare's is not born among labouring, uneducated, servile people," though a lower type of genius might exist "among the working classes" (48-49)?

- consider Woolf's explanations for why there are so few extant literary works by female authors prior to the eighteenth century (48-50). Can you generate any alternative explanations?

- what does Woolf mean by the following claim? "It was the relic of the sense of chastity that dictated anonymity to women even so late as the nineteenth century" (50).

- do you agree that "everything is against the likelihood that [a work of genius] will come from the writer's mind whole and entire" (50) and that, accordingly, the artist needs both solitude and emotional support (or at least the absence of hostility) (52-56)? (Woolf is essentially arguing that the best art is created in the absence of opposition.)

- are the feminists among us comfortable making generalizations about masculinity, as Woolf’s narrator does (55)?

- what does the narrator apparently consider the most likely outcome for the female artist whose creative drive meets uniform resistance from a hostile, sexist society?

- does Mary Beton believe that women and men face the same public opposition when trying to become successful artists?

- how does Mary Beton respond to the notion that a genius, irregardless of sex, should be able to disregard contrary, hostile opinion to their art?

- do you agree that the best art emerges from an "incandescent" mind that only infrequently betrays the author's own "grudges and spites and antipathies" (56)?

Chp. 4

- Woolf’s narrator continues the argument of the previous chapter that the best art is created by an unfettered, “incandescent mind” by elaborating how “fear and hatred” can fracture art before completion (58). Her evidence lies, firstly in the poetry of Lady Winchilsea and Margaret Cavendish, who both allow anger to burst forth in their poetry. Once more, consider: is the best art devoid of obvious emotion?

- what shared circumstances apparently allowed both poets to write?

- according to the narrator, what fact attached to writing novels and translating classics allows female writers to gain some small measure of respect?

- what implicit critique does Woolf’s narrator level at history books?

- why, presumably, did women write more fiction and prose than poetry and plays?

- for those familiar with Austen’s novels, do you agree that she always writes “without preaching” (68)?

- what female author does Austen praise the most for powerfully modeling successful writing?

- Woolf's narrator says it was “impossible for a woman to go about alone” in the early nineteenth century, then qualifies her claim how? Also, can you recall exceptions from Austen’s work that suggest greater mobility for at least fictional characters than Woolf’s narrator allows for actual women of the period?

- Woolf’s narrator claims that Charlotte Brontë’s genius could have surmounted Jane Austen’s, except for what obstacle? Can those of you familiar with other writings by Woolf identify moments where her own frustration breaks through the surface of the narrative?

- Woolf’s narrator declares that one must have immediate experience of many things, like Leo Tolstoy, if one wishes to effectively describe those things. In “The Art of Fiction” (1884), novelist Henry James had claimed that a genius needs only “the faintest hints of life” to transform “the very pulses of the air into revelations.” In a passage which anticipates Woolf’s own use of spider webs, James constructs experience as a “huge spider-web, of the finest silken threads, suspended in the chamber of consciousness and catching every air-born particle in its tissue.” Unlike her, however, he thinks a writer of genius can merely glimpse a thing—catch it in the web of consciousness—and then allow the imagination to compellingly elaborate the glimpsed experience. What do you think?

- does Woolf destabilize or reify the notion of truth?

- do those of you familiar with Jane Eyre agree with this narrator’s observations about the novel’s weaknesses—and those of Charlotte Brontë as a writer?

- what preoccupations does Woolf’s narrator consider stereotypically male, and which female?

- does Woolf’s narrator actually identify in those novels by Austen and Brontë the features which presumably helped them attain the pinnacle of achievement (74)?

- can you conceive of an art form which is distinctly feminine (or masculine), which expresses—to use Woolf’s language—“the poetry” (77) of a particular sex? (Note that Woolf’s narrator remains unsure that the novel serves the female writer better than the epic or the poetic play.)

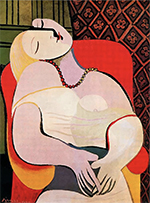

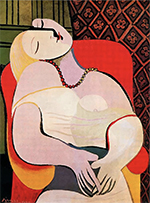

The Dream (1932)

Pablo Picasso

Dr. Paul Marchbanks

pmarchba@calpoly.edu

![]()