Fault Lines

“‘He is all fault who hath no fault at all:

For who loves me must have a touch of earth.’”

("Lancelot and Elaine," ll.132-33)

Points for Reflection

"The Holy Grail" (1869, dated 1870)

- the monk Ambrosius shares with Percivale his conviction that all the knights of the Round Table, be they “good” or “bad,” are stamped “with the image of the King,” a condition he earlier connects with “courtesy” (ll.22-28). Is Ambrosius correct, or have we seen in the tales thus far any exceptions?

- does “The Holy Grail” suggest that romantic ardor and relationship are always a distant second -- morally speaking -- to such heroic and noble ventures as that undertaken by many of Arthur’s knights?

- according to “The Holy Grail,” can moral righteousness coexist for very long with material (bodily and/or social) concerns? Does one necessarily subsume or destroy the other?

- do those who actually see the Holy Grail benefit from the experience?

- why exactly does Arthur decry his knights’ departing on this particular quest? Does this betray in Arthur an inattentiveness to spiritual and holy matters?

- "The Holy Grail” draws a pretty clear demarcation between the miraculous features of the Holy Grail (clearly aligned with Christianity, given the nature of the cup) and the pagan power of that “remnant” strong in “old magic” who imprison Bors for describing his quest as divinely-driven and Christ-centered (ll.657-73)? In light of this dichotomy, where does the tale seem to place Merlin?

- why does that which Percivale sees and touches vanish, whereas Galahad is able to touch such things indefinitely (ll.378-439, 503-7)?

- does the story suggest that Percivale made the right decision in going on the quest?

- whose description of Lancelot’s moral fibre are we to take as truth, Lancelot’s own (ll.763-849) or Arthur’s (ll.761-62, 869-883)?

- is this story the antithesis of RB’s Andrea del Sarto’s “A man’s reach should exceed his grasp, or what’s a heaven for?” Does it place everyone in their place, suggesting that not everyone should strive for the highest?

"Pelleas and Ettarre" (1869)

- is it a fatal mistake for Arthur to require of his knights that they be devoted to a single woman, if any woman at all?

- why are both the rise and fall of Pelleas’s passions so extreme? What about the way in which he looks at and thinks of women makes him so vulnerable?

- what is to blame for the dramatic change visible in Pelleas towards the tale’s end? In answering, consider whether his noble strivings find stronger root in his love of Ettarre or his worship of King Arthur (ll.144-49).

- Ettarre refers derogatorily to Pelleas’s virtue as “‘fulsome innocence’” (l.258). Would it be inappropriate to suggest that she and Guinevere—who in “Lancelot and Elaine” claims that she needs a fallible man with “‘a touch of earth’” (l.133)—are actually more similar than different?

- what do you imagine Pelleas says in the lines left unwritten between l.570 and l.571?

- is Pelleas’s final status primarily a product of circumstance, a tragic flaw in himself, or moral failure in others?

"The Last Tournament" (1871, 1872)

- Lancelot counters Arthur’s suggestion that they temporarily switch positions with the reflection that it would be better if he (Lancelot) pursued the Red Knight (Pelleas) while Arthur stayed to officiate at the coming tournament (ll.108-11). Lancelot does, however, yield to the king’s wishes. Did Arthur misjudge? Should he have heeded his own dream (ll.120-25)?

- what in Nature foreshadows the coming upheaval/change?

- does “The Last Tournament” read as a glorification of or diatribe against martial violence?

- what exactly is the “‘broken music’” to which the court fool, Dagonet, refers when he quips with Tristram (ll.265-67)? Of what does Tristram, ironically, sing (ll.275-84)? Does this approach to life serve Tristram well?

- what does Dagonet mean when he says that the star representing Arthur, though invisible during the day, makes “‘a silent music up in heaven’” (ll.332-49)?

- Dagonet, who obviously respects Arthur, still calls him a fool in the midst of his own clowning (ll.354-58). Consider the blame Tristram places on King Arthur and the supposedly unrealistic vows to which he held his knights (ll.649-98); does it echoe the blame articulated by Vivien and Pelleas. Has this chorus of three voices, by this point, overwhelmed Arthur’s optimism and noble ideals? Has the reader been convinced that Arthur is, indeed, an idealistic fool?

- is the incident related in lines 419-87 a part of Tristram’s dream? Is it a vision of real, distant events?

- Tristram has rationalized his affair by alluding to Guinevere’s and Lancelot’s adultery (ll.560-73), and by deprecating Arthur’s foolish, high-minded idealism (ll.649-98). Does the story as a whole support Tristram’s approach to life?

- why does/might Queen Isolt, husband to Mark, finally yield to Tristram’s caresses, despite understanding full well the “free love” doctrine he elaborates in lines 577-715?

"Guinevere" (1859)

- did Arthur see Guinevere as primarily a virtuous symbol or as passionate lover?

- does Arthur’s kind condemnation of Guinevere come across as just? As configured by Tennyson, does fault lay squarely on her for both her affair and the fall of Camelot?

- what do the enigmatic lines 41-45 of “Guinevere” suggest about the high moral, social, and aesthetic standards of the Round Table? Does this insight shape any other part of the tales we’ve read thus far?

- do the nuns hosting the incognito Guinevere correctly read the significance of her beauty?

- should we take the magical tales told by the little novice to be an accurate rendering of events in Arthur’s life (ll.229-68, 275-303)? Have there been enough proofs of the fantastic that we can now accept this telling at face value?

- does Guinevere’s repeated self-criticism throughout this tale succeed in exonerating her in the reader’s eyes in the same way she wins grace from the nuns?

- does the reader see Arthur with the same eyes as Guinevere? Does he indeed lack the passion and romance which she seeks?

- does Arthur himself live by the oath required of his knights (ll.464-80)?

- does Tennyson suggest that the oath required of Arthur’s knights is impractical (ll.464-80)?

- does Arthur indict himself in lines 509-23?

- decide for Guinevere which word more appropriately describes her actions, “would” or “could” (l.639).

- does the text entire encourage the reader to accept Guinevere’s conclusion that Arthur, because “highest,” was “most human” of all those she knew (ll.643-44)?

- does Guinevere’s final course of action bring her peace? [her decision to become a nun does not eliminate the inner combat between “hoping” and “fearing” (l.685) that she can absolve herself and be reunited with Arthur in the afterlife, though the final line suggests that after being Abbess for three years she passes “To where beyond these voices there is peace” (l.692).

"The Passing of Arthur" (1869, though 11.170-440 existed previously in AT's Morte d'Arthur (1842)

- why is Gawain the perfect knight to appear in Arthur’s dream and speak the words he does (ll.29-37)?

- why is it appropriate that the final battle be described in such “weird” (l.95) terms? What about this battle separates it out from all others Arthur has waged (ll.65-117)?

- how would it have changed the Idylls for Tennyson to have made a more fully rendered—visible and palpable—villain in the character of Mordred? If either Mordred, the Cornish King Mark, or Vivien had appeared more often and worked evil more consistently, what would the Idylls have lost?

- discuss the significance of some of the various question, mysteries, and/or enigmas in this last tale.

- unpack the meaning of lines 154-58.

- for what various reasons does Bedivere repeatedly hesitate to get rid of Excalibur?

- does Arthur’s rationalization of the changes going on about him (ll.408-10) hold water, within the context of the collection?

- the last section of “The Passing of Arthur” clouds the issue of Arthur’s fate (ll.347-48, 423-69). Why might Tennyson do this?

"To the Queen"

- does the final section, “To the Queen,” demystify the enigma which is the Idylls? Is Tennyson’s intention now clearer? Is the collection’s parabolic drift defined in full?

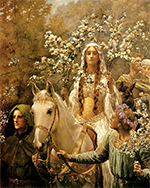

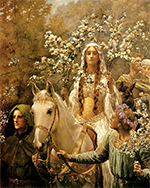

The Maying of Guinevere (1917)

Philip Ralley

Dr. Paul Marchbanks

pmarchba@calpoly.edu

![]()