Not Your Own Hero

"God whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks in our conscience, but shouts

in our pain: it is His megaphone to rouse a deaf world" (91).

C. S. Lewis' The Problem of Pain (1940)

Points

for Reflection

The Bible: Matthew 16:24-26

- what graphic imagery does v. 24 evoke, and why apply this to the life of the believer?

- can you make sense of the paradox in v. 25?

- what does Jesus imply is humanity's default approach to life, one he attempts to correct with pointed rhetorical questions in v. 26?

The Bible: Philippians 4:4-9

- is Paul, the presumed writer of Philippians, recommending apathy when he calls his audience to "not be anxious about anything" (v.6)?

- how might one reconcile the call to "rejoice in the Lord always," in all circumstances (v.4), with the exhortation to focus only on what is "true" and "noble" (v.8)? Is Paul recommending partial attention, some form of self-imposed blindness?

- instead of providing specific examples of the kinds of things practicing Christians should contemplate, Paul provides a string of undefined, nebulous concepts including "pure" and "lovely" (v.8). Look closely at these adjectives, in whatever English translation you're using, and consider which of these are culturally determined--and thus highly variable across time--and which refer directly to an unchanging truth or moral bedrock.

The Bible: Romans 14:1-23

- is Paul providing specific proscriptions and prescriptions regarding Christian behavior in this passage?

- do you think the central idea behind this chapter should be applied to areas of human experience besides food and holidays? To what areas of life should this principle not apply?

- alluding to the Levitical proscriptions against eating "unclean" animals, Paul writes that though he now considers no food to be unclean in God's eyes, he will not eat certain foods in certain situations. Why not?

- what key assumption about human relationships undergirds the core ethic of verses 13-22?

- does this chapter in Romans constitute a call to moral relativism?

Flannery O'Connor's "The Church and the Fiction Writer" (1957), 807-12

- is it possible to replace the word "Catholic" with the more general label "Christian" when reading this essay without altering too much O'Connor's intended meaning? Where does this switcheroo work, and where does it not?

- how does O'Connor define the "eye" when considering that which is appropriate material for the writer of fiction (807 bot)? What limitations does she place on the eye of the Christian/Catholic writer? Does she believe that there are certain things that such a writer should be unwilling to look at squarely (808-810)?

- what might O'Connor mean by "the presence of grace as it appears in nature" (809)?

- O'Connor claims that contemporary Catholics' leanings towards Manichaeism--their tendency to separate "nature and grace" (or the material body and the spiritual world) as far apart from one another as possible--leads to both a narrow view of the supernatural and an inclination to see reality (as depicted in the Arts) as either "the sentimental" or "the obscene" (809). What does she cite as the dangerous consequences of such polarized vision?

- does O'Connor see the process of redemption as instantaneous, or a gradual process (809)? Does her perspective map onto that in Philippians 2:12?

- does O'Connor's claim about sexuality in the '50s apply equally well to pervasive American attitudes towards sex in our own day? Do we pursue coitus the same way we pursue porn--primarily as "an experience for its own sake," one which "leaves out the connection of sex with its hard purposes" (809)?

- do you agree that narrative arts produced by faithful Christians should "reinforce our sense of the supernatural by grounding it in concrete observable reality" instead of anchoring it in "sentiment" and "pious cliche" (810, 809)?

- O'Connor suggests that the Christian author's writing process might be spiritually fruitful for the author, yet result in a literary product that fosters sin in its reader (810). Her "fix" for this quandary is to allow the Church to censure the Arts (810). Can you envision any other ways out of this conundrum? Also, does Romans 14:13-23 apply?

- why does O'Connor feel it necessary to claim what seems quite obvious, that "A belief in fixed dogma cannot fix what goes on in life or blind the believer to it" (811)?

- O'Connor recommends that the Catholic Church find a body of readers willing to recognize in fiction something "besides passages that they consider obscene" (811 mid). Consider this plea within the context of the larger Christian church, putting aside traditional denominational subdivisions for the moment. Do western Christians today appear more willing to judge film, literature, and music according to a standard of decency than to explore such Arts with moral criteria in mind?

- do you sometimes find yourself so "offended and scandalized" by elements of certain stories that you are unable to recognize anything redemptive about them (811)?

- do you agree with O'Connor's claims that, "It is when the individual's faith is weak, not when it is strong, that he will be afraid of an honest fictional representation of life, and [that] when there is a tendency to compartmentalize the spiritual and make it resident in a certain type of life only, the sense of the supernatural is apt gradually to be lost" (811-12)?

- consider O'Connor's claim that fiction "transcend[s] its limitations only by staying within them" (808) and that the Catholic writer reveals mystery by describing truthfully what he sees (810). What is she getting at through these apparent paradoxes?

Flannery O'Connor's "Some Aspects of the Grotesque in Southern Fiction" (1957; 1965), 813-21

- Flannery O'Connor implies that she is one of those "for whom the ordinary aspects of daily-life prove to be of not great fictional interest" (813). She is less interested in the typical/normal than the atypical/abnormal (814), preferring the deeper if eccentric realism that concerns spiritual verities to a shallow realism of fact only (814-15). Such "grotesque" realism might contain "strange skips and gaps" in the narrative, along with elements of "mystery and the unexpected," while retaining an "inner coherence" faithful to individual human psychology and spiritual experience (815). Do you share this preference? Consider the types of film and television towards which you gravitate . . .

- why does O'Connor claim that the "social sciences have cast a dreary blight on the public approach to fiction" (814 top)?

- what once-hidden aspect of human experience has ridden the wave of realism in twentieth-century fiction, according to O'Connor (814 mid-bot)?

- O'Connor notes that one's definition of "realism" hinges on what one considers to be "the ultimate reaches of reality," that many post-Enlightenment optimists convinced of science's ability to (eventually) rid human experience of all suffering focus their attention on the agents of that suffering--on economic, social, psychological, and other quantifiable variables (815 bot). She, by contrast, believes that human life--while describable--remains inherently mysterious because it stands atop a great mystery we only partially understand (816 top). As a Christian writer whose life rest on faith in Divine Grace, then, is O'Connor primarily interested in what we do completely understand as humans, or what we do not? Is she more interested in probability or possibility (816)?

- why does O'Connor claim that writing grotesque fiction is, in one way, easier than writing the kind of realistic fiction produced by Henry James (816 bot)?

- does O'Connor call authors to be compassionate, to place feeling over morality (817 mid)? (For those familiar with C. S. Lewis, would he agree? See pp. 32-33 of The Problem of Pain).

- what definition of prophecy, as it applies to the novelists, does O'Connor offer up (817 bot), and what does she mean when she casts herself with other writers as a "realist of distances" (817 bot, 819 top)?

- O'Connor writes, in 1957, that Southern writers can identify "freaks" so readily because they retain a theological conception of the "whole" human (i.e. soul, as well as body and mind) against which the freak is measured (817 bot). Is this true today? Do the majority of those living in the South see reality through a theological lens? Are they, like Southerners sixty years ago, "Christ-haunted" even when not "Christ-centered" (818 top)?

- does O'Connor identify herself as one who speaks "with" or "counter to" her own era's "prevailing attitudes" (819 bot)?

- O'Connor provocatively asserts that if a reader's heart is in the right place, s/he will indeed find her/his heart "lifted up" by reading her stories (819 bot), and that her fiction points to the "the redemptive act," though it also highlights the high cost of such restoration (and often doesn't detail the actual restoration itself, just its beginning) (820). Do you agree?

- when O'Connor claims that "distortion" is necessary for certain writers to get their "vision" across to the reader, what does she mean (816-17, 821 top)?

- is it possible to reconcile O'Connor's call to create "grotesque" fiction filled with atypical scenarios with the Biblical call to fill one's mind with "whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable . . . [with] anything [that] is excellent or praiseworthy" (Philippians 4:8)?

Flannery O'Connor's "Good Country People" (1955), 263-84

- this tale opens with a sketch of Mrs. Freeman that emphasizes her intractability (263). Are she and Mrs. Hopewell at all similar, or quite opposite?

- what assumption underlies Mrs. Hopewell’s idealistic talk about the Freemans and other “good country people” (264-65)?

- what do Mrs. Hopewell’s thoughts concerning her daughter reveal about her own values (266-69)?

- why did Joy change her name to “Hulga,” and why is she uncomfortable when Mrs. Freeman uses it (266-67)?

- why might O’Connor include those cryptic moments when Hulga angrily quotes French philosopher and priest Nicolas Malebranche (268) and when her mother looks at and is befuddled by a passage about science in one of Hulga's philosophy books (268-69)? What does each enigma suggest about Hulga's interests and values?

- why does Hulga comically insert herself into her mom's conversation with Mrs. Freeman (273 bot, 274 mid)?

- what strategies does the Bible salesman effectively employ in his dealings with Mrs. Hopewell (269-72), then later with Hulga (275-81)?

- Hulga seems shame as an meaningless artifact, a product of a less-evolved, past age of human development. What does she hope to do with Manley Pointer's shame (276), and what has she presumably done with her own (281)?

- how does Hulga respond to Manley Pointer's suggestion that she must be brave to live with such an obvious disability, presumably trusting in God to provide for her (277)?

- how experienced is Hulga, romantically speaking, and how does her response to intimate physical contact slowly change (278-82)?

- why does Hulga’s face turn red the first time the Bible salesman says he wants to see where her wooden leg “‘joins on’” (277), and then lose color the second time he makes this request (280-81)? Is either reaction ironic, given her character?

- why might Mr. Pointer ask for an affirmation of affection with such determination (280)?

- what words from Manley deliriously flip everything on its head for Hulga (281), and which of his subsequent actions violently reshape her assumptions yet again (282-83)?

- why might "Manley" collect . . . what he collects?

- does the story as a whole support Hulga’s assumption that she has “true genius,” and the Bible salesman only an “inferior mind” (276 bot)?

- what does our last glimpse of Hulga suggest about her current, internal state of being

- does Hulga's wooden leg serve a symbolic function, or is it merely a practical prosthesis?

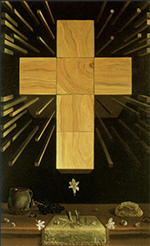

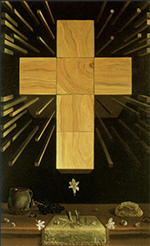

Arithmosophic Cross (1952)

Salvador Dali

Dr. Paul Marchbanks

pmarchba@calpoly.edu

![]()