Fact or Fable?

"People muth be amuthed, Thquire, thomehow . . . they

can't be alwayth a working, nor yet they

can't

be

alwayth a learning'" (35).

Charles Dickens' Hard Times (1854)

Points for Reflection

C. Dickens' Hard Times (1854), Book 1

- not until the end of chapter two does the narrator provide a direct and unequivocal judgment of the utilitarian educational system promulgated by Thomas Gradgrind and the as yet unnamed “third gentleman.” Speaking of the poor schoolmaster Mr. M’Choakumchild and his extensive, systematic training in facts, the narrator adds, “Ah, rather over-done, M’Choakumchild. If he had only learnt a little less, how infinitely better he might have taught much more!” (10). What various indications does Dickens give us, prior to this overt statement, that the utilitarian system is less than laudable?

- how does Dickens’s use and definition of the term “fancy” differ from Coleridge’s in Biographia Literaria?

- what examples of fancy does Dickens provide?

- why might Dickens configure Louisa as staring into the fire at the end of Book I, chp. 8 (44-45) instead of gazing at something else?

- do those characters uncomfortable with the powers of the imagination (e.g. Mr. Bounderby, Tom Gradgrind, etc.) consider fancy to be equally dangerous for boys and for girls?

- how does Dickens go about quickly shaping the reader’s opinions of the very different “Sissy” Jupe and Louisa Grandgrind?

- in what ways does Mr. Gradgrind’s appearance (5) and his residence at Stone Lodge (12) reflect and reiterate his character? How does the residence of Mr. Gradgrind differ from that of Sleary (12-13)? Which structure might Ruskin prefer?

- consider closely the various strategies Dickens employs to create humor in the narrative. Which prove most amusing, and why?

C. Dickens' Hard Times (1854), Book 2

- does Dickens deal in two-dimensional portraiture to an annoying, or an entertaining, degree? Which characters are flattened by his one-note depiction, and to what end?

- to which characters does Dickens actually grant depth and complexity, and why?

- Mr. Gradgrind originally appears to be a dry, focused, myopic man who lives by a strict code. How does Dickens later complicate this characterization (76-77, etc.).

- the narrator implies that Harthouse is an evil influence, and even aligns him with Satan (93, 136-37). The narrator also claims Harthouse has no real malevolence or even selfish intent (136), that he’s merely a very careless individual. How are we, then, to judge this character?

- what attributes of Louisa most strongly attract the attention of James Harthouse?

- how cold and calculating is Louisa, really?

- how realistic is Louia’s ignorance of the great gap between classes (120, 121)?

- how do the overtly stated opinions, commentary, and obvious foreshadowings of Dickens’ narrator shape the narrative? How does the presence of this active agent shape characterization, verisimilitude, dramatic tension, and tone? Does the narrator hand-deliver any subtle or implicit lessons?

- how do the narrator's opinions concerning characters to whom we've just been introduced, such as Harthouse and Slackbridge, shape the story's dramatic tension?

- can you identify examples of free indirect discourse in the narrative, where the narrator’s own voice and perspective abruptly disappear into the obvious biases and thoughts of a given character?

C. Dickens' Hard Times (1854), Book 3

- does Dickens project succesfully engage women's rights? Does either Louisa or Sissy emerge as a feminine ideal?

- Louisa’s passive decision to marry Bounderby constitutes one of the novel’s central tragedies. What of her husband? Why did Bounderby seek out marriage with Louisa? Is this text’s relative silence on this subject quite loud? Are his reasons, that is, something Dickens would be unwilling to articulate aloud in a work of fiction?asdf

- by the novel’s end, which of Dickens’ clearly, loudly articulated values can neatly pair with similar values voiced by other Victorian writers?

- does Dickens grant utilitarianism and political economy a fair trial, or attempt to totally upend them?

- has the the notion of law and public opinion been so thoroughly interrogated by the novel’s end that Tom’s family and Sissy could be considered to act justly in trying to save him from the justice system?

- should the fantastic elements, exaggerated tone, and severe didacticism of this novel win it categorization as a fable?

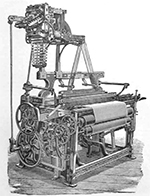

19th-Century Power Loom

Dr. Paul Marchbanks

pmarchba@calpoly.edu

![]()