![]()

chps 1-7

1. does Henry James make essentializing observations about his French characters? Does he, that is, seem interested in employing facile stereotypes to make it easier to distinguish between Newman and those Frenchmen and women he meets?

2. to what degree is Newman aware of the various devices being used by Noémie and her father, M. Nioche, to flatter their new patron? Is he the naïve simpleton his narrator claims he is not (68)?

3. what purpose is served by James’s inclusion of Newman’s trip across the European continent during the summer months, a trip spent primarily in the company of Babcock? Do the chapters which follow suggest Newman learned more about himself during his time with this fellow American?

4. does Newman seem, thus far, a dramatic or comic figure? Is he a genius, or a fool? Does James’s hero “deeply appeal to our sympathy” yet? (6, James employs these words in the novel’s Preface—please do not read it until you’ve finished the novel—where he explains that he hoped to generate such readerly sympathy for his protagonist.)

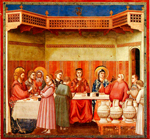

5. reconsider the opening to chapter two, in which we find Newman reseating himself on a circular divan at the Louvre art museum in Paris and turning his attention to Paul Veronese’s “The Wedding at Cana” (1562-63). Is James’s decision to mention this particular painting significant, in light of what follows in the succeeding chapters? (Click on the left-hand image at the bottom of this page for a larger version.)

6. in chapter three, Mr. Tristram suggests that Claire de Bellegarde (also known as Madame de Cintré) is extremely proud (52), an issue which Newman later raises to himself in her presence (94). Do Claire’s interactions with Newman support or counter Mr. Tristram’s assertion? Does the reader see anything Newman does not?

chps 8-14

1. does the narrator wish us to judge harshly the naïvete on display in Newman’s habit of thinking the best of those he meets and befriends (151)? Consider the narrator’s attitude towards Newman up through this week's reading.

2. does Henry James appear to be exploding or affirming the notion of distinct, nation-specific characteristics (excluding language) that make it easy to distinguish the American man or woman from the French man or woman?

3. in sentence two of chapter thirteen, the narrator tells us that he actually knows Newman better than Newman knows himself (168). Does this throw into question the validity of Newman’s perceptions in general? Recall that in chapter three, Mrs. Tristram noted her inability to determine whether Newman was in fact “simple” or “deep” (44). Which does he appear to be thus far?

4. why does Count Valentin de Bellegarde continue to pursue Nóemie Nioche, despite what he learns about her character and general dearth of propriety?

5. Newman, decidedly not a religious man, employs religious language as he considers changing Valentin into a businessman back in America. He wants to help Valentin “‘find salvation’” (233) and glows with the “idea of converting this irresistible idler into a first-class man of business” (237, my emphasis). Does what we know of these two men up through (but not beyond) page 238 suggest that Newman will prove a failed or successful messiah? (As always, I’m not looking for a correct answer—don’t read ahead here—just a well-documented, reasoned response.)

The Marriage at Cana (1562-63)

Paul Veronese

Dr. Paul Marchbanks

pmarchba@calpoly.edu